by Elizabeth de Cleyre

One of my MFA professors once brought in a freshly-printed book deal and said, “One day, if you’re lucky, you might have one of these.” Aside from one hour in the presence of a contract, the two-year curriculum did not include a comprehensive guide to the ins-and-outs of publishing. Most graduate programs focus on the writing itself, not what happens after its written. And yet this naive graduate student had once hoped a book deal would be handed out with diplomas.

Most writers cobble together an understanding of publishing and promotion through articles and books, lacking cohesion and leaving holes in one’s understanding. The often mystifying process feels that much more bewildering when discussed in bits and pieces. There are the known unknowns—that which we know we don’t know, like how advances actually work and how much to expect—and then there are unknown unknowns—all that we don’t even know we don’t know.

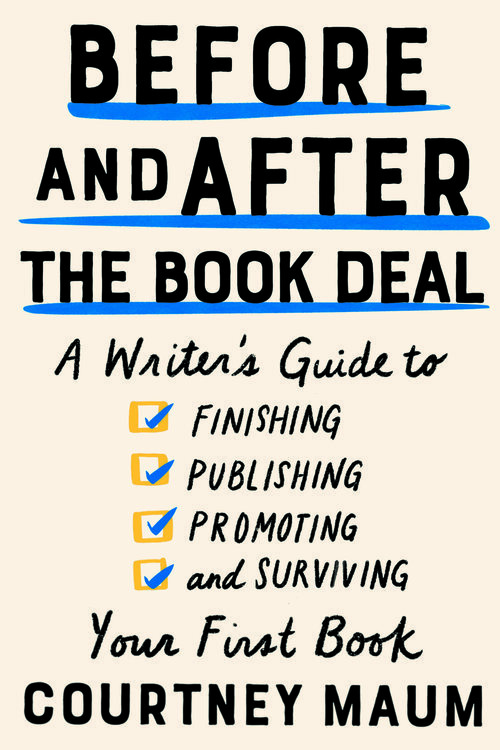

Thankfully, Courtney Maum breaks down the mystifying process of publishing in promotion in her latest book, Before and After the Book Deal: A Writer's Guide to Finishing, Publishing, Promoting, and Surviving Your First Book. The comprehensive guide is equal parts entertaining and enlightening, informed by her own career as a novelist and extensive research and interviews with agents, editors, writers and authors.

In November, Maum delivered the endnote address at The Loft’s Wordsmith Conference in Minneapolis, where she pointed out the precariousness of publishing and offered practical advice for redefining success.

I ran into Maum at the elevator, and quickly blurted out how much I adored her chapbook Notes from Mexico, a slim book that stayed with me long after its publication in 2012. Her funny and heartfelt debut I Am Having So Much Fun Here Without You garnered praise from seemingly everyone, including Vogue, Vanity Fair, Elle, O Magazine The New York Times Book Review, Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal. In Maum’s second novel Touch, a trend forecaster for a tech company envisions people moving away from smart devices and back toward “in-personism;” I count the remarkably prescient and palpable book among my favorite novels. Her latest was published by Tin House in July of 2019, which Margaret Leonard of Dotters Books called, “a wonderful coming-of-age story, the heat of Costalegre makes it the perfect summer read.”

Now in the depths of winter, Maum generously answered questions via email about her first work nonfiction, the importance of writing residencies and workshops, dispensing sage advice in her free newsletter, and running a collaborative retreat in Connecticut.

Elizabeth de Cleyre: What inspired you to write Before and After the Book Deal: A Writer's Guide to Finishing, Publishing, Promoting, and Surviving Your First Book?

Courtney Maum: In America, there are tons of books that purport to teach you how to write well enough to get a book deal, and there are lots of classes and conferences you can attend for the same purpose. But when you actually achieve your dream and get that book deal? Good luck finding any advice! I wanted to write this book because it doesn’t exist and I felt it really needed to. What does life look and feel like as a published author? How do you navigate the very weird transition between being your book’s writer and then becoming its author (and its ambassador and social media manager and PR manager and…)

EDC: The experience of publishing and promoting a book about publishing and promoting a book seems so meta. Has the publishing and promotional experience been any different from your last four books? Was there anything you learned in the writing of this book that helped you with the publishing and promotion process?

CM: Meta indeed! This was a different kind of publishing experience, for sure. It’s my first book of non-fiction, and it’s also the first book of mine that has content that I can easily teach, so touring for this book has been an entirely different ball game. I’m working with students, teaching at writing centers, lecturing. There’s something of a built-in audience for Before and After the Book Deal, so I know when I do events that people will actually show up, whereas with novels, you never know what to expect. If you get five people, you’re super lucky.

This year, I published two books: Before and After the Book Deal and Costalegre. I’ll never do it again, it’s honestly too much work having books six months apart, but one of the positives is that I haven’t had the free time to worry about how either book is doing. I just do what I need to do and move on. There quite literally isn’t time to sweat the small stuff—that has been a positive for me, because you don’t get far in publishing when you are obsessed with control—so many factors are out of your hands, sometimes it’s just healthier to let go, trust your team, and see what happens.

EDC: In the section entitled "When the show goes on the road" you mention how audience members (usually men) will ask touring authors advice on how to get their own books, and you suggest directing them to the "'writing reference” section in the bookshop where they can find this book." How many times has this happened to you? Has it happened to you on this tour?

CM: Incredibly, this is probably the ONE tour where I haven’t had “that guy” ask this question. It’s amazing, right? Before, it didn’t matter which novel I was touring for, I always had someone who would be like, okay, I don’t really care what you’re saying, the real question is how can you help me? I guess having non-fiction out posits you as an expert in your subject. The questions during my Q&As (and they are actual questions! Not comments cloaked as questions) have been serious, thoughtful, savvy. The audience members, too.

EDC: You recently mentioned that early feedback on the book idea was to self-publish. Why? Did you consider it? Why did you want to work with a traditional publisher?

CM: I didn’t consider it for an instant. I self-published a collection of short stories in my late twenties and it was a very positive experience that I considered a stepping stone to traditional publication. I don’t think that certain gatekeepers understood the shape this book was going to take when they were imagining it as a published object. They thought it was going to be an exposé about the industry or a memoir—my “publishing memoir.” (You can’t see me, but I’m laughing.) It wasn’t until I got the entire thing under their noses where they were like, oh, wow. Now we get it. This is actually a really empowering book.

EDC: How long did it take you to find a publisher, and how did the connection with Catapult come about?

CM: It didn’t take long at all. Our submission list was really small and Catapult responded right away— Julie Buntin, my editor for this book, saw the value in the project immediately because she herself is both an editor and a writer. This being said, when it was on submission, it was only “After the Book Deal.” Catapult rightly argued that the book would find a wider audience if I added a “Before” section to it so that we could offer people a really comprehensive resource. I think that was a smart call.

EDC: Before and After the Book Deal is easily the most comprehensive and compelling book on the publishing industry that I've read, one that should be required reading for all writers. You mentioned interviewing nearly 200 individuals for the book. How did you condense all that research? What was the process like? How did you decide how to structure it?

CM: Thank you! Gosh, it was such a great process. Usually the writing of a book is so lonely—not so with this book. From the get-go, I was in touch with authors and publishing professionals WAY above my station. So many people were so generous, giving me their time and sharing their knowledge before I even had a book deal for the project.

I wrote the table of contents first. Then I did a beat sheet, basically, sketching out what my intro to each section would be about and putting placeholders for either the exact contributor I wanted or what kind of quote I wanted, then I’d find the right person to offer tonality of quote. I pulled from my own contacts maybe 40% of the time, and for the rest of the book, I asked people to recommend people—I wanted to make sure that I was talking beyond my circle of colleagues and friends. There really wasn’t anything cut from the book. Except my run-on sentences.

EDC: Was there anything you came across in your research that really surprised you? Or did it feel like you were mostly affirming and structuring what you already knew or had experienced?

CM: I think what surprised me, as you intuited, was also an affirmation—what surprised me was how ready people were to talk about this topic, about what life is really like off of social media, behind the curtain, for the published writer. We are educated to be hashtag grateful all the time, and people were just so ready to say, you know what? Sure, publishing is a privilege but it is really hard. It makes us raw. It makes us vulnerable. Things don’t go the way we want. When they do go the way we want, we don’t know what to aim for any more. Success is always a moving target in this industry and that can be hard to sit with.

EDC: Part of what makes the book compelling and hard to put down is the injection of humor. You've written witty columns for Tin House, taught online courses through Catapult on how to be funny on the page, and have an upcoming AWP panel on humor in fiction. Much of publishing advice is serious and a little stiff, so why did you decide to incorporate comic elements? Was it difficult, given the subject matter or publishing standards for this kind of book?

CM: What would have been difficult would have been to write this book without humor. Writing is hard enough, who wants to read a somber guide about writing and publishing? I think that a sense of humor is the number one tool you’ll need in your survival kit if you want to be a published writer. There is just so little you can control, so many arbitrary things that happen, lucky strikes that come out of nowhere, terrible luck that ruins your book launch—if you don’t have a sense of humor about the whole thing, or learn to develop one, I am not exaggerating—you are going to have a nervous breakdown.

EDC: You founded a collaborative retreat in Norfolk, Connecticut for people working in the arts. What was the inspiration for The Cabins, and how has it evolved?

CM: My husband is a filmmaker, and it was on the short film festival circuit that I first got the idea for The Cabins. I thought, gosh, isn’t this ridiculous, all these short film filmmakers who will never meet the short story writers whose work they are in a perfect position to adapt. Originally, I envisioned The Cabins as a collaboration between writers and filmmakers, but it turns out that filmmakers are impossible to pin down. Much like actors, they are in the gig economy and have to be able to drop everything at a moment’s notice. It’s hard for them to commit to anything. So when I finally did create the program, I made it truly interdisciplinary. It’s like an adult summer arts camp where everyone learns from each other. We get out of our silos. We learn things we didn’t even know we wanted to learn.

EDC: In addition to writing books, you also lecture and teach at workshops like Tin House Winter Workshop and the Loft Wordsmith Conference, among others. Can you speak to the role or importance of writing residencies and workshops?

CM: Your success in the publishing industry is going to be largely based on your ability to forge and maintain relationships. Going to writing workshops and conferences teaches you how to be a good listener, it teaches you how to small talk, how to give feedback, how to take feedback. For many, the writing workshop is one of the first places where we get a glimpse of how our work will be received by the outside world. But perhaps more importantly, sometimes we meet someone at these things—even in passing—who changes our approach to writing. Or to life. I took a one-hour master class with Michelle Hoover back at the Wesleyan Writers Workshop in 2011 and I am telling you, it changed my writing. I started getting published. That one hour, with one great teacher, made me a better writer.

EDC: What books are you reading and recommending lately?

CM: Thank you for asking! I just finished Jacqueline Woodson’s Red at the Bone. My God. I’ve never read such a gorgeous book. I just adored it. I am currently reading Sally Rooney’s Normal People. I wanted to wait until the hype died down to do so. I pre-ordered Jenny Offill’s Weather and I’m sure I’ll be a wreck when it arrives because I will wish that I could write a book like that. And I can’t wait for my friend Marie Helene Bertino’s Parakeet to come out this spring!

EDC: What's next for you? What are you working on now?

CM: I’m excited about this newsletter I’ve launched called “Get Published, Stay Published.” People can sign up on my website CourtneyMaum.com – it’s free. I’m getting ready for the June edition of The Cabins, and I’m revising a memoir about depression. And I’m still promoting Costalegre and Before and After the Book Deal around the country.

Find more of Courtney Maum’s books on her website, https://www.courtneymaum.com/books

Elizabeth de Cleyre is a writer and editor. Find her at cedecreative.com.